반응형

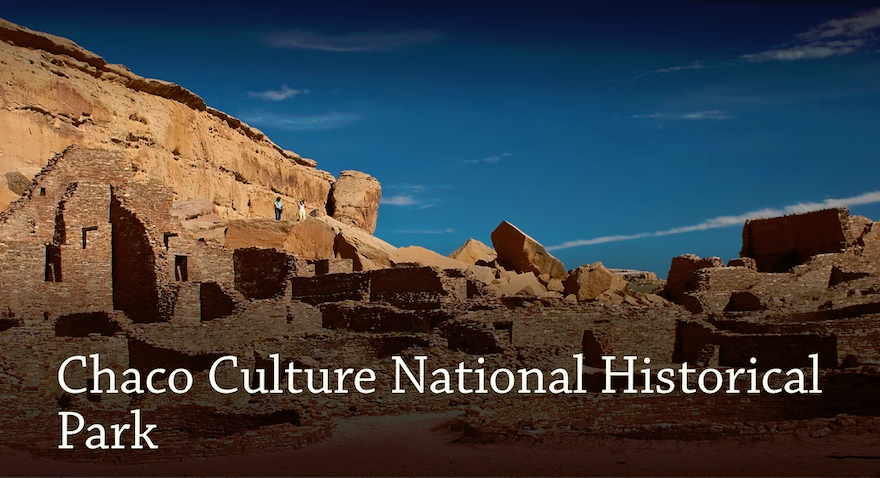

차코 문화 국립역사공원(Chaco Culture National Historical Park)

.

천년전 미국 인디언들도 대형 석조건축 아파트를 짖고 살았습니다. 미개했을 것으로 추측되던 미국 인디언들에 대한 편견이 일거에 가시는 순간이었습니다. 4개주가 만나는 포코너가 있는 파밍톤(Farmington)에서 구글맵을 따라 운전해가다 보면 과연 이런곳에 국립공원이 있을까 의문이 들 정도의 비포장도로가 나오기 시작합니다. 4륜차가 없으면 운전하기 겁날정도로 도로상태는 엉망입니다. 중간에 구글맵은 엉뚱한 길로 인도하는데 길가에 망가진 바퀴며 망가진 자동차 흔적이 나타나 구글맵을 포기하고 뜨문뜨문 세워진 이정표를 따라 가다보면 공원입구에 100년은 족히 되었을 포장도로가 나오고 공원관리사무소에는 불친절한 직원하나가 퉁명스럽게 입장료 25불을 징수합니다. 오라고 홍보하는게 아니라 마치 오지 말라고 부아리는 느낌입니다. 각설하고, 얼마 지나지 않아 미국인디언의 가공할 위대함에 놀라고 맙니다.

.

차코 문화 국립역사공원(Chaco Culture National Historical Park)은 미국 뉴멕시코주의 서북부의 산환분지(San Juan basin)에 있는 차코 캐니언(Chaco Canyon)에 서기 900년부터 1150년까지 아나사지 인디언이 건설한 문명입니다. 많은 대형 건물이 세워 졌고 인근의 마을들로 직선 도로가 뻗어 있습니다. 1907년, 루스벨트 대통령이 미국 국가기념물(National Monument)로 지정했고, 1980년 국립역사공원으로 지정되었습니다. 그리고 1987년 유네스코 세계문화유산에 등재되었습니다.

.

1150년경부터 계속되는 가뭄으로 인해 아나사지 인디언들은 이 곳을 버리고 생활여건이 좋은 곳으로 떠나기 시작했습니다. 현재의 나바호(Navajo), 쥬니(Zuni), 푸에블로 (Pueblo) 인디언이 살고 있는 지역으로 이동한 것으로 추정하고 있습니다. 차코 캐니언은 페허가 되었고 많은 대형 건물은 600년 동안 먼지를 뒤집어쓰고 흙더미에 덮힌 채로 방치되었다가, 1846년에 재발견되었습니다. 1896년에 본격적인 고고학적 발굴작업이 시작되어 푸에블로보니타(Pueblo Bonita)가 먼저 발굴되었습니다.

.

약 2400개에 달하는 유적지가 발견되었지만 발굴된 유적지는 소수에 불과합니다. 고고학 기술이 더 발전될 후대에 체계적으로 발굴할 수 있도록 유적지 보존에 많은 노력을 기울이고 있습니다. 차코의 인디언들은 한 건물에 수백 개의 방이 있는 지금의 아파트와 유사한 다층의 대형 건물을 지었습니다. 벽은 사암을 벽돌 모양으로 잘라서 층층이 쌓았으며, 다층 구조로 짓기 위해서 서까래용 통나무가 다량으로 소요되었습니다. 사용한 통나무 수는 약 20만개였을것으로 추정되는데, 이 지역은 비가 오지 않는 황야여서 큰 나무가 자라지 않습니다. 그들은 80km 거리에 있는 산에서 통나무를 운반해왔는데, 그 당시에는 마차가 없었고 바퀴도 발명되지 않았으니 인력에 의존했을 것입니다. 집단 거주지의 위치를 산밑이나 강가 같은 곳으로 하지 않고 왜 황야의 고원지대에 건설했는지는 수수께끼입니다.

.

대표적인 건물 유적지는 우나 비다(Una Vida), 킨 크렡소(Kin Kletso), 푸에블로 알토 (Pueblo Alto), 푸에블로 보니토(Pueblo Bonito) 등이 있습니다. 차코인들은 중심지로부터 뻗어나가는 직선도로를 여러 개 만들어 주변의 다른 마을과 연결했습니다. 항공사진과 인공위성으로 관측한 바에 따르면, 차코 케니언을 중심으로 거미줄갈이 사방으로 뻗아나간 직선도로가 약 650km라고 합니다. 운송수단으로 쓸 만한 동물이 없었고 바퀴나 마차가 발명되기 이전에 폭이 10m나 되는 직선도로를 계획적으로 만든 이유가 무엇인지도 수수께끼입니다. 도로를 만들 때에는 산이나 언덕같은 장애물이 있으면 이를 피해 돌아가는게 일반적인데, 계단을 만들더라도 직선을 고집한 이유도 알 수가 없습니다.

.

차코인들은 달과 태양의 움직임을 관찰하여 춘분과 추분의 날짜를 알았고 천문학 지식을 건축공사와 농사짓는 일에 적용했습니다. 파하다 뷰트(Fajada Butte)라고 부르는 산의 정상에 천문관측용 유적이 있습니다. 해의 위치에 따른 그림자 이동을 관측하여 동지와 하지, 춘분 추분을 알아내는 나선형의 암각화(Petroglyph)가 있는데 이를 썬대거(Sun dagger)라고 부릅니다. 이 유적은 현재는 일반인의 출입을 금지하고 있습니다. 토기를 만드는 기술이 있었고 터키석 공예품은 남쪽 멕시코의 밀림과 태평양 연안에까지 거래되었습니다.

.

푸에블로 보니토(Pueblo Bonito)는 차코 캐니언의 유적지 중에서 가장 큽니다. 푸에블로 보니토의 뜻은 “아름다운 마을”입니다. 4층 구조로 지은 대형 아파트 같은 건물로서 651개의 방과 40개의 키바(Kiva)를 가진 건물이며, 남향으로 지었는데 반원의 직경부분이되는 전면의 벽이 춘분과 추분때의 해뜨는 지점과 해지는 지점을 이은 선에 일치되도록 배치했습니다. 이 건물은 주거용이라기보다는 종교나 정치적 목적으로 추정됩니다. 5년의 발굴기간 동안에 6만여 점의 유물이 나왔고 뉴욕 박물관에 보관되어 있습니다.

.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park is a United States National Historical Park in the American Southwest hosting a concentration of pueblos. The park is located in northwestern New Mexico, between Albuquerque and Farmington, in a remote canyon cut by the Chaco Wash. Containing the most sweeping collection of ancient ruins north of Mexico, the park preserves one of the most important pre-Columbian cultural and historical areas in the United States. Between AD 900 and 1150, Chaco Canyon was a major center of culture for the Ancestral Puebloans. Chacoans quarried sandstone blocks and hauled timber from great distances, assembling fifteen major complexes that remained the largest buildings ever built in North America until the 19th century. Evidence of archaeoastronomy at Chaco has been proposed, with the "Sun Dagger" petroglyph at Fajada Butte a popular example. Many Chacoan buildings may have been aligned to capture the solar and lunar cycles, requiring generations of astronomical observations and centuries of skillfully coordinated construction. Climate change is thought to have led to the emigration of Chacoans and the eventual abandonment of the canyon, beginning with a fifty-year drought commencing in 1130. Comprising a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the arid and sparsely populated Four Corners region, the Chacoan cultural sites are fragile—concerns of erosion caused by tourists have led to the closure of Fajada Butte to the public. The sites are considered sacred ancestral homelands by the Hopi and Pueblo people, who maintain oral accounts of their historical migration from Chaco and their spiritual relationship to the land. Although park preservation efforts can conflict with native religious beliefs, tribal representatives work closely with the National Park Service to share their knowledge and respect the heritage of the Chacoan culture. The park is on the Trails of the Ancients Byway, one of the designated New Mexico Scenic Byways.

.

Chaco Canyon lies within the San Juan Basin, atop the vast Colorado Plateau, surrounded by the Chuska Mountains to the west, the San Juan Mountains to the north, and the San Pedro Mountains to the east. Ancient Chacoans drew upon dense forests of oak, piñon, ponderosa pine, and juniper to obtain timber and other resources. The canyon itself, located within lowlands circumscribed by dune fields, ridges, and mountains, is aligned along a roughly northwest-to-southeast axis and is rimmed by flat massifs known as mesas. Large gaps between the southwestern cliff faces—side canyons known as rincons—were critical in funneling rain-bearing storms into the canyon and boosting local precipitation levels. The principal Chacoan complexes, such as Pueblo Bonito, Nuevo Alto, and Kin Kletso, have elevations of 6,200 to 6,440 ft (1,890 to 1,960 m). The alluvial canyon floor slopes downward to the northwest at a gentle grade of 30 feet per mile (6 m/km); it is bisected by the Chaco Wash, an arroyo that rarely bears water. The canyon's main aquifers were too deep to be of use to ancient Chacoans: only several smaller and shallower sources supported the small springs that sustained them. Today, aside from occasional storm runoff coursing through arroyos, substantial surface water—springs, pools, wells—is virtually nonexistent.

.

Archaic–Early Basketmakers - The first people in the San Juan Basin were hunter-gatherers: the Archaic–Early Basketmaker people. These small bands descended from nomadic Clovis big-game hunters who arrived in the Southwest around 10,000 BC. More than 70 campsites from this period, carbon-dated to the period 7000–1500 BC and mostly consisting of stone chips and other leavings, were found in Atlatl Cave and elsewhere within Chaco Canyon, with at least one of the sites located on the canyon floor near an exposed arroyo. The Archaic–Early Basketmaker people were nomadic or semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers who over time began making baskets to store gathered plants. By the end of the period, some people cultivated food. Excavation of their campsites and rock shelters has revealed that they made tools, gathered wild plants, and killed and processed game. Slab-lined storage cists indicate a change from a wholly nomadic lifestyle.

.

Ancestral Puebloans - A map of the American Southwest and the northwest of Mexico showing modern political boundaries. Overlaid over them are four colored and labeled territories: "Anasazi", "Hohokam", "Petaya", and "Mogollón". Anasazi land is colored green.

.

Anasazi sites in the Southwest - By 900 BC, Archaic people lived at Atlatl Cave and similar sites. They left little evidence of their presence in Chaco Canyon. By AD 490, their descendants, of the Late Basketmaker II Era, farmed lands around Shabik'eshchee Village and other pit-house settlements at Chaco.

.

A small population of Basketmakers remained in the Chaco Canyon area. The broad arc of their cultural elaboration culminated around 800, during the Pueblo I Era, when they were building crescent-shaped stone complexes, each comprising four to five residential suites abutting subterranean kivas, large enclosed areas reserved for rites. Such structures characterize the Early Pueblo People. By 850, the Ancient Pueblo population—the "Anasazi", from a Ute term adopted by the Navajo denoting the "ancient ones" or "enemy ancestors"—had rapidly expanded: groups resided in larger, more densely populated pueblos. Strong evidence attests to a canyon-wide turquoise processing and trading industry dating from the tenth century. Around then, the first section of Pueblo Bonito was built: a curved row of 50 rooms near its present north wall. Archaeogenomic analysis of the mitochondria of nine skeletons from high-status graves in Pueblo Bonito determined that members of an elite matriline were interred here for approximately 330 years between 800 and 1130, suggesting continuity with the matrilineal succession practices of many Pueblo nations today.

The cohesive Chacoan system began unravelling around 1140, perhaps triggered by an extreme fifty-year drought that began in 1130; chronic climatic instability, including a series of severe droughts, again struck the region between 1250 and 1450. Poor water management led to arroyo cutting; deforestation was extensive and economically devastating: timber for construction had to be hauled instead from outlying mountain ranges such as the Chuska mountains, which are more than 50 miles (80 km) to the west. Outlying communities began to depopulate and, by the end of the century, the buildings in the central canyon had been neatly sealed and abandoned.

.

Some scholars suggest that violence and warfare, perhaps involving cannibalism, impelled the evacuations. Hints of such include dismembered bodies—dating from Chacoan times—found at two sites within the central canyon. Yet Chacoan complexes showed little evidence of being defended or defensively sited high on cliff faces or atop mesas. Only several minor sites at Chaco have evidence of the large-scale burning that would suggest enemy raids. Archaeological and cultural evidence leads scientists to believe people from this region migrated south, east, and west into the valleys and drainages of the Little Colorado River, the Rio Puerco, and the Rio Grande. Anthropologist Joseph Tainter deals at length with the structure and decline of Chaco civilization in his 1988 study The Collapse of Complex Societies.

.

Athabaskan succession - Numic-speaking peoples, such as the Ute and Shoshone, were present on the Colorado Plateau beginning in the 12th century. Nomadic Southern Athabaskan-speaking peoples, such as the Apache and Navajo, succeeded the Pueblo people in this region by the 15th century. In the process, they acquired Chacoan customs and agricultural skills. Ute tribal groups also frequented the region, primarily during hunting and raiding expeditions. The modern Navajo Nation lies west of Chaco Canyon, and many Navajo live in surrounding areas.

.

Excavation and protection - The first documented trip through Chaco Canyon was an 1823 expedition led by New Mexican governor José Antonio Vizcarra when the area was under Mexican rule. He noted several large ruins in the canyon. The American trader Josiah Gregg wrote about the ruins of Chaco Canyon, referring in 1832 to Pueblo Bonito as "built of fine-grit sandstone". In 1849, a U.S. Army detachment passed through and surveyed the ruins, following United States acquisition of the Southwest with its victory in the Mexican War in 1848. The canyon was so remote, however, that it was scarcely visited over the next 50 years. After brief reconnaissance work by Smithsonian scholars in the 1870s, formal archaeological work began in 1896 when a party from the American Museum of Natural History based in New York City—the Hyde Exploring Expedition—began excavating Pueblo Bonito. Spending five summers in the region, they sent more than 60,000 artifacts back to New York and operated a series of trading posts in the area.

.

In 1901 Richard Wetherill, who had worked for the Hyde expedition, claimed a homestead of 161 acres (65 ha) that included Pueblo Bonito, Pueblo del Arroyo, and Chetro Ketl. While investigating Wetherill's land claim, federal land agent Samuel J. Holsinger detailed the physical setting of the canyon and the sites, noted prehistoric road segments and stairways above Chetro Ketl, and documented prehistoric dams and irrigation systems. His report went unpublished and unheeded. It urged the creation of a national park to safeguard Chacoan sites.

The next year, Edgar Lee Hewett, president of New Mexico Normal University (later renamed New Mexico Highlands University), mapped many Chacoan sites. Hewett and others helped enact the Federal Antiquities Act of 1906, the first U.S. law to protect relics; it was, in effect, a direct consequence of Wetherill's controversial activities at Chaco. The Act also authorized the President to establish national monuments: on March 11, 1907, Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed Chaco Canyon National Monument. Wetherill relinquished his land claims.

.

In 1920, the National Geographic Society began an archaeological examination of Chaco Canyon and appointed Neil Judd, then 32, to head the project. After a reconnaissance trip that year, Judd proposed to excavate Pueblo Bonito, the largest ruin at Chaco. Beginning in 1921, Judd spent seven field seasons at Chaco. Living and working conditions were spartan at best. In his memoirs, Judd noted dryly that "Chaco Canyon has its limitations as a summer resort". By 1925, Judd's excavators had removed 100,000 short tons of overburden, using a team of "35 or more Indians, ten white men, and eight or nine horses". Judd's team found only 69 hearths in the ruin, a puzzling discovery as winters are cold at Chaco. Judd sent A. E. Douglass more than 90 specimens for tree-ring dating, then in its infancy. At that time, Douglass had only a "floating" chronology. it was not until 1929 that a Judd-led team found the "missing link". Most of the beams used at Chaco were cut between 1033 and 1092, the height of construction there.

.

In 1949, the University of New Mexico deeded over adjoining lands to form an expanded Chaco Canyon National Monument. In return, the university maintained scientific research rights to the area. By 1959, the National Park Service had constructed a park visitor center, staff housing, and campgrounds. As a historic property of the National Park Service, the National Monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. In 1971, researchers Robert Lister and James Judge established the "Chaco Center", a division for cultural research that functioned as a joint project between the University of New Mexico and the National Park Service. A number of multi-disciplinary research projects, archaeological surveys, and limited excavations began during this time. The Chaco Center extensively surveyed the Chacoan roads, well-constructed and strongly reinforced thoroughfares radiating from the central canyon.

.

The richness of the cultural remains at park sites led to the expansion of the small National Monument into the Chaco Culture National Historical Park on December 19, 1980, when an additional 13,000 acres (5,300 ha) were added to the protected area. In 1987, the park was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. To safeguard Chacoan sites on adjacent Bureau of Land Management and Navajo Nation lands, the Park Service developed the multi-agency Chaco Culture Archaeological Protection Site program. These initiatives have identified more than 2,400 archeological sites within the current park's boundaries; only a small percentage of these have been excavated.

.

+++

반응형